The integration of LSU football finally came in 1971, and it officially began with the start of the 1972 season, Charlie McClendon’s 11th season as the head coach of the Tigers when the first two black signees in school football history were eligible to play, at last.

In those years, freshmen – regardless of color – were deemed ineligible and could not play varsity until their sophomore seasons.

Racial integration for LSU football was a long time coming, about 10 years later than it should have been, according to federal legislation.

However, unlike most of the rest of the nation, the deep south was hard-headed and set in its ways. Schools in the Southeastern Conference, LSU included, spent most of the 1960s fighting to stave off integration, undermine it legislatively, or even outright defeat it, before finally realizing the fight to maintain segregation was a battle against the Federal government and, for the most part, public sentiment, they simply could not win. Especially if they wanted to compete with, and have a chance, to beat teams from the North, West and Mid-West that had begun integration years before.

Louisiana, in particular, also had a relatively progressive governor in John McKeithen, a protégé’ of the Kingfish himself – Huey Long.

McKeithen loved LSU sports – especially football – as much if not more than Long himself did. McKeithen wanted to not only desegregate Louisiana, LSU and its sports. McKeithen also wanted to win, and he knew that winning would mean it would be necessary to recruit the best, most outstanding football players from the state of Louisiana and across the nation – no matter what they looked like or what the color of their skin was.

Not many black high school football players in Louisiana wanted to, or even thought about, going to play for LSU.

So, in 1972, McKeithen compelled McClendon to turn his attention to the national scene, and to reach out to coaches within the college football fraternity that could help him identify at least two black players who LSU could recruit.

One of the coaches McClendon turned to was Duffy Daugherty, the head coach at Michigan State. Daugherty coached the Spartans from 1954 through 1972 and had been recruiting black athletes to the Spartans for years, including a black quarterback named Jimmy Raye. In fact, Daugherty ran what was called the “The Underground Railroad.” It was named after Harriet Tubman’s way of transporting non-free black Americans to freedom and safety, Daugherty was known to have the recruiting pipeline to the best black athletes in the United States wherever they played and resided.

Based on the feedback from Daugherty and other fraternal coaching brothers, as well some inside information McClendon received, he pointed McKeithen to Lora Hinton, an All-American running back from Virginia.

So, McKeithen did what any other typical state governor would do. He picked up the phone and made the recruiting call directly to Hinton.

Longtime Louisiana sports journalist, Marty Mulé, who was also a columnist for Tiger Rag and a decorated Hall of Fame columnist for the Times-Picayune, characterized McKeithen’s phone call to Hinton in a story he wrote for the Baton Rouge Advocate about two years before he passed away in 2014 at the age of 73:

“A strange voice boomed through the interstate telephone line: ‘Lora, this is Gov. John J. McKeithen of Loos-i-ana. We have a fine school down here — and a good football team. Why don’t you come down and give us a visit?’”

Hinton’s incredible speed and shiftiness were more than enough to attract the attention of a lot schools, but Hinton had other qualities that appealed to LSU and McKeithen.

Hinton said he chose to sign with LSU in 1971 mainly because he wanted the “big-time” opportunity to play for a team like LSU, he loved the brand, he wanted to stay out of the cold and because he said he was not afraid to embrace the challenge of crossing the color line of LSU football.

In that order.

“I wanted to play ball at LSU. Play in Tiger Stadium. It was the opportunity of a lifetime. And I would do it all over again if I could,” Hinton said.

“Apparently, there was a nation-wide search to find the black athletes to play for LSU. I suppose the Federal government was interested in LSU picking up some black athletes, and they were putting pressure on LSU football to sign some black players. There were very few black athletes in LSU sports at the time and none on the football team.”

So, Hinton, from Chesapeake, Virginia, became the first black football signee in LSU history, signing in the spring of 1971 despite offers from Notre Dame, Ohio State, Purdue, Duke and a host of other schools.

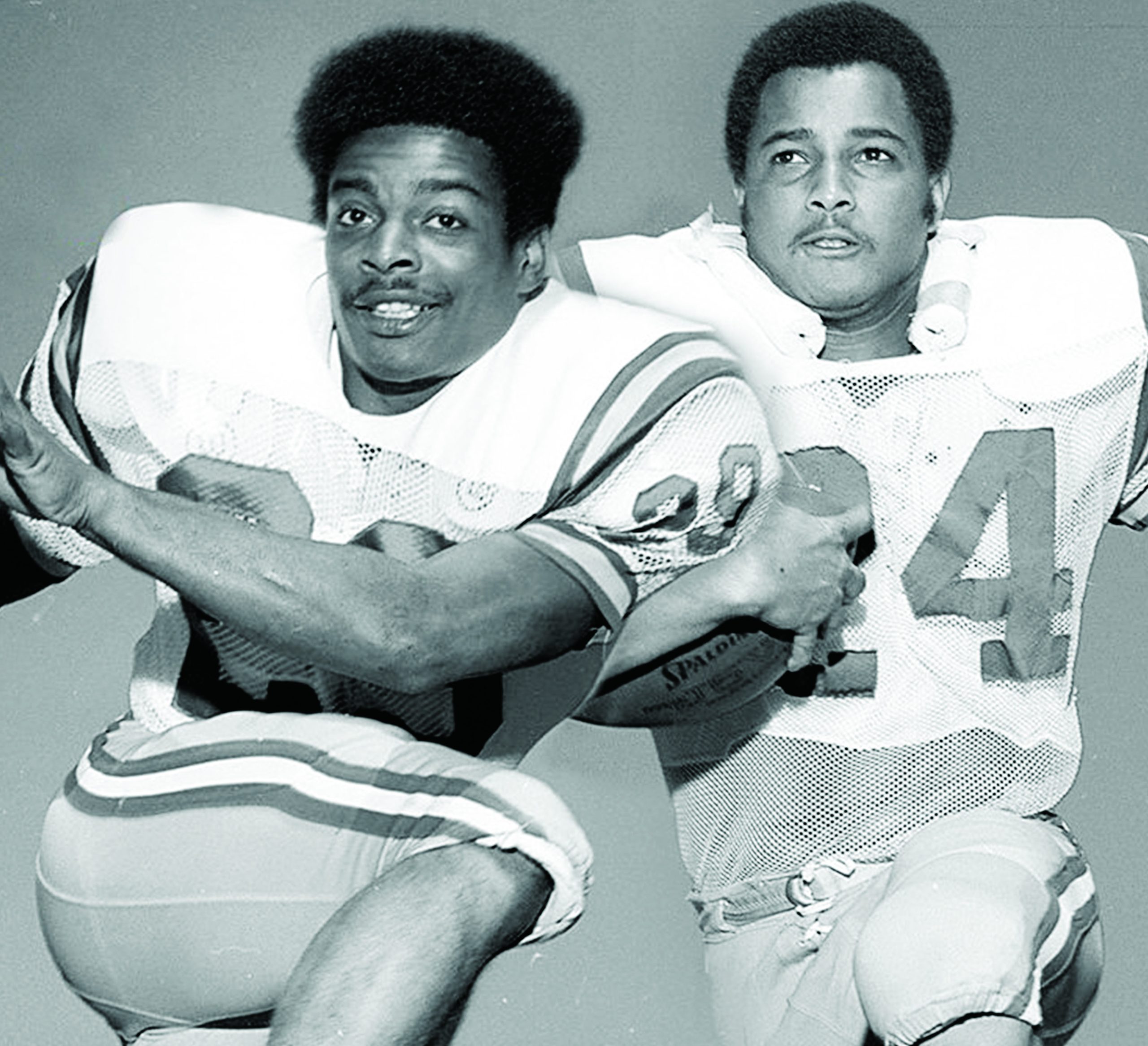

Hinton was followed soon after by Mike Williams of Covington, LA, who ended up being an All American at LSU and the No. 22 overall pick in the NFL Draft in 1975.

The first-round draft choice of the San Diego Chargers, Williams started for San Diego for 8½ seasons at left and then right cornerback before finishing up his career by playing for the Los Angeles Rams for half a season. Williams was a nine-time All Pro in the NFL.

Hinton had suffered a serious knee injury during his senior year at Great Bridge High School. But he still attracted the attention of nearly every major college football program in the country that was already racially integrated – basically meaning most of the major colleges above the Mason-Dixon line because of his speed, quickness and game film.

Unbeknownst to Hinton, LSU had simultaneously turned its eyes also to another black football player within the state of Louisiana. Williams, the third-leading rusher out of Covington High School had seemingly disappeared from LSU’s recruiting radar for some reason despite his unmatched speed and gaudy statistics. Williams first seemed to be headed to Tulane, but then opted to sign with Southeastern Louisiana University in the spring of 1971 to stay close to home, be close to his Mom and Dad and to be close to where his girlfriend lived.

Back in the late 1960s and early 70s, the Louisiana High School All-Star Game was played in Tiger Stadium.

Williams was invited to play. And he stole the show, so to speak.

Not too long after, LSU coach Don “Scooter” Purvis, who had played on LSU’s 1958 national championship team and was a running backs coach for Cholly Mac, approached Williams and asked him if he wanted to play at LSU.

The Tigers were paying attention to Williams again. Something that took Williams by surprise.

“People who looked like me did not play at LSU,” Williams said.

He never thought LSU would seriously make him an offer. Williams, an only child, was dead set on staying close to home, anyway. So, he really did not give LSU’s second overture, no matter how serious it seemed now, much thought. But Purvis explained to Williams because Southeastern was, at the time, in a different division of college football than LSU, the rules permitted LSU to still sign him if he wanted to be a Tiger.

Hinton did not know about Williams at the time. Williams did not know about Hinton.

They would get to know each other shortly afterwards and would build a life-long relationship that began as trailblazing pioneers.

Neither Hinton nor Williams thought about themselves as pioneers or trailblazers when they arrived at LSU in 1971. But they accept that moniker and realize how true the statement is.

“The mindset of black students back in that day was, if you give us an opportunity we can achieve just like anybody else. So, there was a certain pride. They do call us pioneers, trailblazers. I’ll accept that. But to me, the people before us were the true pioneers. My big brothers and sisters, and the students at Southern University that walked into the drug stores, and demanded to be served at the lunch counter. . . I’m not sure I had that, you know what I mean? I was treated a little bit better than they were,” Hinton said.

Hinton and Williams are still very close to this day.

“We are like brothers. We were all like brothers, the whole team,” Hinton said.

How could they not be?

They both say they never really thought about it at the time, but in retrospect, Hinton and Williams both agreed that they, along with other black players who first joined LSU in the early 1970s – Hinton, first and Williams in 1971, followed by two black recruits who signed in 1972, Silas Smith and Richard Romain, both from New Orleans, and then in 1973 the foursome was joined by Robert Dow, Terry Robiskie and Carl Otis Trimble.

Dow was also a blazing wide receiver at LSU who Purvis started recruiting by mistake when Dow was a sophomore at St. Joseph’s Catholic School in Jackson, Mississippi.

Purvis was there to scout one of Dow’s teammates but saw this impressive kid playing defensive back and inquired about him. He found out he was only a sophomore but that did not deter Purvis.

“He kept coming back and coming back. I didn’t really know all that much about LSU,” Dow said.

“But the more I learned over time, the more I liked it, the more I saw the opportunity.”

By the time Dow was a senior every major school in the South, including Tennessee, Alabama and both Mississippi State and Ole Miss, among others, were after the 185-pound speedster.

However, LSU held a special place in Dow’s mind, he said, by then, much like it did for Hinton.

“It was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up,” Dow said.

“And I am so happy I went there instead of Tennessee (his early favorite) because of Condredge Holloway. Man, that guy could spin the ball. I was a fast receiver and wanted to catch balls from him all day long. And they threw it back then, too. Most teams did not.

“But I ended up choosing LSU because it was actually closer to Jackson than even the two Mississippi schools. That way my family could come to all of my games in Baton Rouge. That was very important to me.”

Hinton, Williams and Dow all say they never felt any racial prejudice or poor treatment from the LSU coaches or players. And that they maintain strong, solid relationships to this day with teammates from back then, both black and white.

“There was no difference. No white and black, not on the football field and not in the dormitory. It was like a fraternity in that we were all truly brothers and are to this day,” Dow said.

Dow also said he was never concerned about racial tension in the deep south.

“I grew up in Jackson, Mississippi. I faced it every day. We learned how to handle it and react to situations if they ever occurred. It never concerned me about going to LSU, and I never had any problems”

Still, the racial barrier had to be cracked originally.

And in order to do that, McKeithen and McClendon turned to Hinton in Virginia for their first black player/ signee.

“My impression when I got down here, I had a visit a with another black athlete from New Orleans, and my impression from him was that nobody wanted to take a chance to come to LSU, to sign with LSU, because there was a lot of history surrounding LSU. I’m not really sure what all that entailed, but a lot of local people were not really interested. I was surprised that this young man was not interested in going to the state university, but I understood where he was coming from given the situation at that time. A lot of unrest in the country, a lot of unrest in Louisiana at the time, everywhere, and Virginia also,” Hinton said.

“People used to accuse me of being from the north, but they didn’t realize General Robert E. Lee was from there and that’s where it all started.”

Despite dealing with the lingering knee injury he suffered in high school, Hinton found success at LSU. He had to redshirt his sophomore because he had major knee surgery early in his non-eligible freshman season. He was a three-year letterman and a starting running back for the Tigers in 1973 and 1974. In 2021, Hinton was enshrined in the LSU Athletics Hall of Fame.

Be the first to comment