By JAMES MORAN | Tiger Rag Associate Editor

Long before anyone called him ‘The Professor,’ Dave Aranda was a mediocre-at-best student.

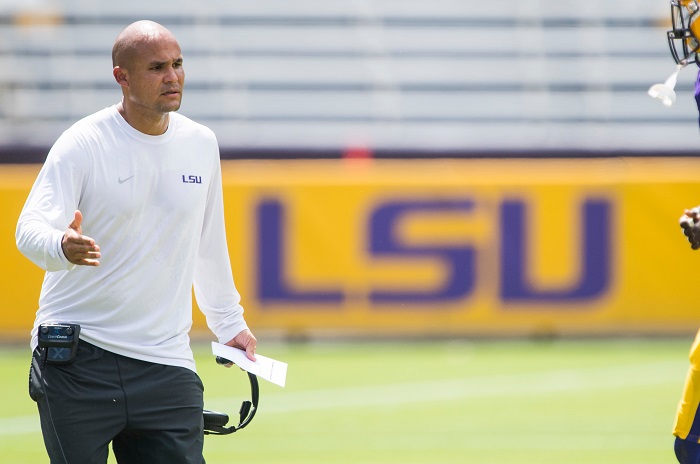

These days the 40-year-old is a venerable whiz kid.

Aranda is considered one of the brightest young minds in college football and an integral part of Ed Orgeron’s proposed masterplan for Southeastern Conference domination.

Orgeron made retaining Aranda his No. 1 priority once LSU Athletics Director Joe Alleva removed that pesky interim tag from his dream job last fall. LSU and Aranda agreed on a new three-year deal that makes him the nation’s highest paid assistant at an average annual salary of $1.85 million.

The results from year one left no doubt of Aranda’s brilliance in Baton Rouge. His new boss calls him “the best defensive coordinator in America” with regularity. His players describe him as a master instructor that took the LSU defense to new heights in 2016.

Some even believe he’s a genius.

LSU allowed the fewest touchdowns among FBS programs in its inaugural season under Aranda. His unit shut out mighty Alabama for three quarters in Tiger Stadium and utterly dominated Heisman Trophy winner Lamar Jackson and Louisville in the Citrus Bowl.

“It’s kind of like you get a double major with football,” defensive end Christian LaCouture says. “Guys in the room make sure we pick his brain because, like you saw last year, what he brought to the table for our defense was crazy. You can’t pay him enough to do it because the way he explains the scheme to you just fires everybody up.”

How did a self-described “marginal student” who graduated high school in 1994 with no plan or college prospects become this renowned mastermind? How did someone who barely played football become one of the game’s premier tacticians? How’d he rise from defensive coordinator at his alma mater Cal Lutheran to the same position at LSU in just 10 years?

The answer to all of these questions begins with hard learning.

KNOWING AND UNDERSTANDING aren’t the same things.

You know something like a Snapple fact or a trivia question. It’s a fleeting piece of information floating about in the subconscious that, if searched for, can be spoken or put into action. It’s enough to pass a test after a night of cramming and then flush out of mind forever.

But is the knowledge so ingrained and internalized that it can be accessed without having to think? That’s the kind of understanding that’s at the heart of everything Aranda believes about teaching.

“That is so true of learning in general,” Aranda says. “We’ll nod our head and we get it, but there’s greater knowledge. That’s what you want to draw out when you’re coaching. You want them to be able to act real confident when they get their cleats in the ground and go.”

SEE ALSO: How Dave Aranda Watches Film

For Aranda, that’s always required taking a lot of notes.

Years ago he began scribbling notes in the margins of every book he reads. Then, once he finishes a section, he’ll transcribe those notes and whole passages he wants to remember in a separate notebook. Eventually, he’ll organize the notes by concept or point — whatever works best for the subject — for later reference.

“Once I do all that, now I’ve got it,” he explains. “Now I know it. If I just read it, I’m not going to remember it. I don’t got it. If I read it at 11 a.m., I’ll forget it by that afternoon. I don’t really learn that good.”

This summer’s annotated reading material only added to a collection that’s been building inside his California family home since his days at Redlands High School. He’s admittedly not good at vacationing, having spent most of his break reading, taking notes and watching old football games on ESPNU.

http://www.tigerrag.com/inside-the-lab-how-dave-aranda-watches-film/

Though his father never played, Aranda fell in love with the game watching the Los Angeles Rams. An avid fandom bloomed despite living in the Bay Area at the height of Joe Montana’s prowess and the 49ers dynasty.

Aranda joined the football team in junior high school, but his career ended before it even began. He stayed with it throughout high school, but chronic shoulder injuries derailed him. He lost count after six procedures and says he never played in a varsity game.

“I always loved being part of a team,” Aranda says of what kept him coming back. “If you’re part of a team, you’re part of a group of guys who believe the same thing that you believe and are working really hard to accomplish a collective goal. When you’re not part of a team, it cuts you pretty deep.”

After graduation came the question that hits like a bucket of ice water: what now?

Aranda coached at Redlands High while earning enough credits to qualify for admission into California Lutheran. He coached linebackers there — on staff with his roommate, Tom Herman — while obtaining a philosophy undergrad degree before moving on to Texas Tech as a graduate assistant.

“To me it was something to get me off the streets and not go down a bad path,” Aranda says. “It was just something to do and I fell in love with it right then.”

His first full-time gig came as Houston’s linebackers coach in 2003. After two seasons there he returned to his alma mater for his first ever coordinator gig. Two seasons there kicked off a whirlwind rise that included stops at Division II Delta State, Utah State, Wisconsin and finally LSU.

The note taking began back in his undergrad days.

Throughout his ascension, Aranda took offseason and even in-semester trips to visit with defensive staffs around the country. His family home is littered with notebooks full of sketches, diagrams and notes from various stops at Arizona, Washington and even a 1999 trip to LSU.

Within those notebooks the concepts and ideas that’d grow into Aranda’s method began to take shape. At first he became entranced with the schematics of his craft. Building defenses and devising gameplans to counteract anything an opposing offense could throw at him.

Only problem: sometimes all those notebooks didn’t contain the answer. Aranda recalls a mobile quarterback from Division III Redlands College that nobody in the league — himself included — could figure out how to get tackled from his time at Cal Lutheran.

Whenever faced with a problem, Aranda would consult his notes or call mentors only to find contradictory advice. Even when two sources presented a similar solution, it was called something else or devised differently.

“Going through all of that was a great experience, but I think that’s different and unique from most,” Aranda says. “There were so many times in those early years where I wished one person would just say, ‘Dave, this is how you do it.’ But I’ve outgrown that. I feel fortunate to have all those mentors and experiences because I think it’s a broader brush.”

It took years, but eventually, Aranda found the answer that he needed.

SOME CALL IT the detective’s curse. Search hard enough for the answer and you’ll miss that it’s been right under your nose the whole time.

For years Aranda poured his heart and soul into devising the perfect gameplan for every opponent. He wouldn’t rest until he had a play to match every one the offense could run, a different alignment for every formation the offense could show and a check to correspond with any possible shifts or variations.

The schemes were utterly brilliant, but that’s not what Aranda remembers. What stuck out was a defense that did too much thinking and not enough playing. Football is a game of inches, and every hesitation can mean major yards.

“I’m critical about that stuff,” Aranda says. “I think it was more about me. I did too much. It was like an offense has this play, we’ll have this play. If they do this, we’ll do that. I had all the answers. The unfortunate thing about that, when you get to the point when you make a players’ game into a coaches’ game, the players don’t have the answers. They didn’t know. They were trying their best, but it was just too much. They were making mistakes, and it’s my fault.”

Sometimes there’s brilliance in simplicity.

Aranda arrived at this conclusion during the 2011-12 offseason sometime around his move from Hawaii to Utah Valley. As he’ll tell you, his previous two units ranked No. 50 and 66 nationally in total defenses. That was enough for the former philosophy student to conduct a thorough self-examination.

“The problem with that approach is a lot of times you’re the only one with the answers,” Aranda says. “That ain’t the deal. It just became a maturity part of it. The longer you went, the more you learned to invest in the players.”

After consulting with mentors, the young coach decided it was time to get back to basics. Since then he’s focused on drilling home the basics to the point they become second nature and then working on them some more.

Basically, he learned to teach to the players the way that he himself had learn. Repetition, repetition and more repetition. Establish a foundation, even if you never have time to go beyond that.

The results speak for themselves. Utah Valley finished No. 14 in total defense during his lone season and his units have ranked top-10 nationally since in four seasons at Wisconsin and LSU.

And LSU’s defense last season, one lauded as brilliant and revolutionary by players, fellow coaches and observers, may have been the simplest one he’s ever coordinated schematically.

Knowing he inherited a veteran unit on its third new leader in as many seasons, he did all he could to be minimalistic and let the seasoned athleticism of his personnel go to work.

Perhaps he’ll built on that foundation this season, he says, but only once the vast crop of first-time starters and newcomers — blank canvasses for him to mold — are able to master the foundation. That’s his process now.

These days it’s Aranda who is hosting the visits from young coaches in search of answers. Coaches from Texas Tech, Oregon and Washington all made summer pilgrimages to learn what they can from college football’s hottest defensive mastermind.

His first bit of profound wisdom is always the same: don’t overthink it.

| Year | School | Total Defense (YPG) | National Rank |

| 2010 | Hawaii | 357.6 | 50 |

| 2011 | Hawaii | 387.4 | 66 |

| 2012 | Utah State | 322.1 | 14 |

| 2013 | Wisconsin | 305.1 | 7 |

| 2014 | Wisconsin | 294.1 | 4 |

| 2015 | Wisconsin | 268.5 | 2 |

| 2016 | LSU | 314.4 | 10 |

| Year | School | Scoring Defense (PPG) |

| 2005 | Cal Lutheran | 18.9 |

| 2006 | Cal Lutheran | 19.1 |

| 2007 | Delta State (Co-DC) | 13.9 |

| 2010 | Hawaii | 25.5 |

| 2011 | Hawaii | 29.1 |

| 2012 | Utah State | 15.4 |

| 2013 | Wisconsin | 19.1 |

| 2014 | Wisconsin | 20.8 |

| 2015 | Wisconsin | 13.7 |

| 2016 | LSU | 15.8 |

1 Trackback / Pingback