Almost 25 seasons after Dale Brown finished his 25-year career as LSU’s head men’s basketball coach, the school’s Board of Supervisors approved Friday at its monthly meeting to name the Pete Maravich Assembly Center court in Brown’s honor.

The vote passed by a vote of 12-3 after nine speakers appeared and a two-hour debate by the Board, after a failed vote of 12-3 to name the court for Brown and former Tigers’ women’s coach Sue Gunter and after a failed vote of 11-4 to table the motion of voting on the court to name the court for Brown.

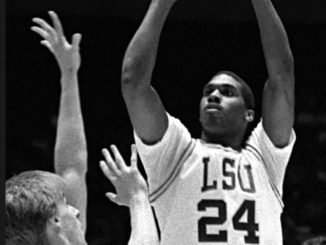

“We’ve had 10 years to talk about this and the reason we’ve talked about it for 10 years was because some folk didn’t want to do (it) for this nigger-loving Dale Brown,” said current LSU Board of Supervisors member Collis Temple Jr., who played for Brown in the final two seasons of his career as the first African American basketball player in LSU history. “He changed the trajectory of the state of Louisiana and the mindset of all the stereotypical negativity.”

Board of Supervisors member Jay Blossman said the rules for a court re-naming needed to be changed to become more transparent and more procedure needed to be established before taking a vote. Lee Mallett, another Board member, said the issue has been discussed for decade in committee and there wasn’t a recommendation to move forward, but the board needed to vote on the issue once and for all.

Board member and former Board chair Mary Werner, while saying Brown represented all student athletes, said she was disappointed not one former female student-athlete spoke on Brown’s behalf. She also said while Brown’s and Gunter’s honors and record are comparable, Werner felt the issue of naming a court should come through the students. She also said the court should be named for a coach who wins a national championship.

“Nothing against Dale Brown, but this is the inappropriate honor at the inappropriate time,” Werner said.

Brown, who turns 86 years old on Halloween and who still lives in Baton Rouge, is the winningest coach in LSU history (448) and is second all-time in the SEC in league victories (238) behind Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp.

Though the fiery Brown, as a little-known Washington State assistant, transformed a destitute LSU program into a perennial NCAA tournament team that advanced to Final Fours in 1981 and 1986, the fight to have the Tigers’ home court named for him has been a behind-the-scenes political battle for decades.

“Awards and honors were never a goal of mine, ” Brown said in a released statement. “My only goals were to build LSU into a national power and to help young men improve their lives.

“Now, though, with the tremendous honor LSU’s Board of Supervisors has just given me – the naming of

Dale Brown Court— I get to use one of the most powerful phrases in the English language: THANK YOU!

“Thank you to the Board of Supervisors for thinking enough of me to make this happen. Thank you to the people of Louisiana who have always allowed me to enjoy such a special relationship with both LSU and this entire state that I have loved for so long. Thank you to the parents who entrusted me with their sons. Thank you to my players and assistant coaches and support staff. Thank you to LSU fans everywhere.

“You have given me the honor of a lifetime. More than that, you have honored me by allowing me to be

part of your lives for so many years now. THANK YOU!”

There has been persistent push from long-time Brown backers, such as national play-by-play TV announcer Tim Brando and Tiger Rag Magazine publisher Jim Engster, to have the court named for Brown.

Brando, a Louisiana native who began his rise to national prominence while working at WAFB-TV in Baton Rouge, addressed the Board of Supervisors at its August meeting. On Friday in Los Angeles where he’ll call the Stanford vs. USC football game Saturday for FOX Sports, an ecstatic Brando credited Board members Temple and Glenn Armentor for finally getting Brown’s name on the court.

“For anyone who against it, just because it happened before you were born doesn’t mean it’s any less significant,” Brando said. “Dale was so far ahead of the curven in humanity and has proven to ahead of the curve with the recent NCAA changes (such as athletes being paid for name, image and likeness) that has affected hundreds of thousands of student-athletes.

“They have the rights they do because Dale shouted from the mountain tops when it wasn’t the popular thing to do. He put himself in a position of being a target in 80s because he dared to go after the `Gestapo’, as he called it (the NCAA).”

Engster, who also is owner and president of the Louisiana Radio Network, spoke to the Board before Friday’s vote.

“Dale Brown was a person not afraid to rock the boat and rock it in a good way,” Engster said. “In the 1990s, he formed a (Dale Brown) foundation to enable (pay for) his players to go back to school (to graduate). He is an ambassador all over the world. He is a man with a remarkable record of achievement.”

There were more reinforcements to also speak on Brown’s behalf including his former players Durand “Rudy” Macklin, Jordy Hultberg and Ricky Blanton as well as Brown’s LSU coaching successor John Brady.

“Dale told me `if you come to LSU you can always say you built something’,” said Macklin, who was recruited out of Louisville in 1976 and was Brown’s first All-American at LSU in 1981. “I came to LSU because of him. I stayed here because of him. He and I together often talked about building this program.

“He brought me to help turn the culture around. LSU was still running from its (racial) past in a sense. He needed to change that. He was the first to put an all-black starting five on the floor and caught hell for it. . .these things led to an increase of minority enrollment, more people of color would come to the games, more people of color became season ticket holders.

“It takes somebody to light the match and Dale Brown did that.”

Hultberg, who was a member of LSU’s 1981 Final Four team along with Macklin and was once an assistant on Brown’s staff, said Brown was “first my coach, my mentor and now my friend.”

“He is a person who has never seen color, he has never seen creed, he just sees human beings,” said Hultberg, who added he was a high school freshman in New Orleans in 1972 when he first met Brown. “He treated us with dignity and respect. He tried to make us well-rounded people.”

Blanton, who led the Tigers to the 1986 Final Four along with the late Don Redden, said Brown “was the brand of LSU basketball for 25 years.”

“What’s interesting to me is what kind of man he was outside of basketball,” Blanton said of Brown. “He is a true humanitarian. Coach Brown is all about helping people. He has changed a lot of lives, impacted a lot of kids.”

Brady, who succeeded Brown and coached LSU for 11 seasons taking the Tigers to the 2006 Final Four, said precedent has been set in honoring other LSU athletes and coaches who have achieved greatness. The school has statues of 1959 Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon, basketball All-Americans Bob Pettit and Shaquille O’ Neal (with one forthcoming of “Pistol Pete” Maravich), women’s basketball coach Sue Gunter and baseball coach Skip Bertman.

“Coach Brown fought the fight against inequality and discrimination at a time where it wasn’t the popular or the appropriate thing to do,” Brady said. “He created a consistent and winning environment LSU never thought possible. He made LSU a national player on the college basketball scene. Coach Brown created and sustained over the years an expectation level for LSU basketball.”

When Maravich died at age 40 in 1988, it was Brown who swayed the Louisiana Legislature and Gov. Buddy Roemer to name the Assembly Center in honor of the son of his predecessor Press Maravich.

As far back as 2004 when former LSU athletic director Joe Dean wrote a letter to the Baton Rouge newspaper The Advocate saying he believed the PMAC home court should be named for Brown, there has been pushback from various Board of Supervisors.

Despite the fact LSU won four regular season SEC championships, one league tourney, had 10 winning seasons including a school-record 31 wins in 1980-81, the fact the Tigers incurred NCAA sanctions under Brown’s watch in the final years of his career was considered a huge black mark against him.

Lester Earl, who played 292 minutes in 11 games for Brown and LSU in 1996-97, transferred to Kansas. Once there, he told NCAA investigators LSU assistant coach Johnny Jones gave him money when he was at LSU.

An NCAA investigation found no evidence that Brown or his assistants paid Earl, but it discovered a former booster Redfield Bryan paid Earl about $5,000.

The NCAA gave LSU a three-year probation with loss of scholarships and official recruiting visits and a one-year postseason tournament ban.

In an August 2007 in a letter to the Advocate, Earl issued an apology to Brown, Jones, and LSU. Earl claimed the NCAA pressured him into making false claims against Brown or else he would lose years of NCAA eligibility.

“I was pressured into telling them SOMETHING,” Earl wrote in the letter. “I was 19 years old at that time. The NCAA intimidated me, manipulated me into making up things, and basically encouraged me to lie, in order to be able to finish my playing career at Kansas. They told me if we don’t find any dirt on Coach Brown you won’t be allowed to play but one more year at Kansas. I caused great harm, heartache and difficulties for so many people. I feel sorriest for hurting Coach Brown. Coach Brown, I apologize to you for tarnishing your magnificent career at LSU.”

A film of Earl’s admission and how the NCAA coerced him to lie was shown to the Board before Friday’s vote.

Brown said long ago he had forgiven Earl.

“The most interesting journey that a person can make is discovering himself,” Brown said in response to Earl’s letter. “I believe Lester has done that, and I forgive him.”

Brown coached 160 players at LSU with 112 of them earning degrees. Through the years, he has kept track of all of them as they became professional athletes in three sports and also doctors, lawyers, engineers, ministers, coaches, teachers, high school principals, business owners, corporate presidents, corporate vice presidents and police officers.

Brown joins an extensive list of former college coaches who have courts where they coached named after them.

It includes Mike Krzyzewskl (Duke), Roy Williams (North Carolina, Eddie Sutton (Oklahoma State), Nolan Richardson (Florida), Billy Donovan (Florida), James Naismith (Kansas), Lute Olson (Arizona), Jim Boeheim (Syracuse), John Wooden (UCLA and Indiana State), Denny Crum (Louisville), Jerry Tarkanian (UNLV), John Thompson (Georgetown), Gary Williams (Maryland), Lou Henson (Illinois and New Mexico State), Bob King (New Mexico), Bobby Cremins (Georgia Tech), Gene Keady (Purdue), Bob King (New Mexico), Indiana (Branch McCracken) and Pat Summit (Tennessee).

Be the first to comment