Nearly 30 years after he exploded on the scene for the Leesville Wampus Cats the legend of Cecil “The Diesel” Collins still hovers over Louisiana’s football history.

In 1995 Collins led his school to its first and only state championship game, was named Louisiana’s initial Mr. Football and had recruiters from LSU, Nebraska and Notre Dame visiting this west central town in hopes of landing his commitment.

He had a military town of about 6,000 people not used to football success going bonkers watching arguably the best high school running back in the nation.

“It was the year we always waited for,” said Chuck Owen, a former player himself, sideline reporter for Wampus Cat games and the author of a detailed history of the program.

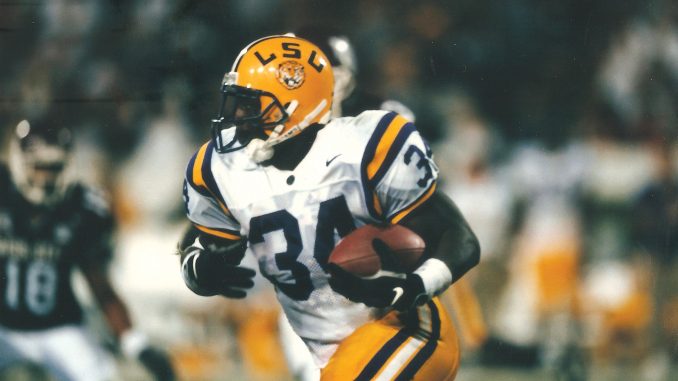

But after a brief but eye-popping, four-game career at LSU – Collins had national broadcasters gushing over his talent and Tiger fans envisioning a national championship — things went off the rails.

He was kicked out of LSU for illegally entering a dwelling, according to news accounts.

Then Collins was convicted of breaking into the home of a woman after a brief stint with the Miami Dolphins.

He spent 13 years in a Florida prison for burglary before being released in 2013.

Today Collins, 46, is an electrician in Houston and, friends say, a changed man who has taken account for his mistakes.

“Great father, great husband and a great man,” said Danny Smith, who was Collins’ head football coach at Leesville and remains close to the former running back.

But 28 years after his season of glory Collins remains outside the Leesville High School sports hall of fame.

Ray Ortiz, president of the Leesville Alumni Association, said the star running back has been nominated for the hall of fame but never gotten the needed votes from the 12-member panel.

Ortiz declined to speculate on how the town’s most famous son is generally viewed.

“He is a legend in this area with regard to his athleticism,” he said.

Left behind is a mixed legacy: giddiness even today among those who watched him run around and over defenders but questions and sadness over how things came undone.

“I would think that many remember him fondly, but they want to know what the heck happened,” said Rick Barnickle, a TV and radio broadcaster who watched Collins’ high school career from 1992-95.

“He had all the talent in the world,” Barnickle added.

“He was the offense,” he said. “They (opponents) didn’t really have an answer for him.”

Lance Guidry, defensive coordinator for the University of Miami, was in his first week as a defensive backfield coach at Leesville after being a defensive back himself at McNeese State University.

Guidry remembers standing behind the defensive backs watching practice.

“Cecil came through the defensive line and got to the second level and he came by me so fast and so violently that I don’t know if I would have tackled that guy and I was fresh out of college,” Guidry said.

Guidry said he has watched lots of running backs up close, including former LSU star Leonard Fournette and Alabama standouts Eddie Lacy and T. J. Yeldon.

“But I have still been the most impressed with Cecil Collins,” Guidry said.

“Just how physically tough he was,” he added.

“The guy would not come out of the game. He practiced harder than anybody I have been around.”

Leesville is about 60 miles west of Alexandria.

In those days around 40% of the team was from military families, which means players came and left depending on their parents’ military status.

Coaches could tell Collins was a special player in the eighth grade, doing things on the football field not normal for someone his age.

The next year coaches at Westlake High School near Lake Charles took notice during a pre-season scrimmage.

“They said ‘Who is that?’ Smith recalled.

“I said ‘I know coach. He has a chance to be really good.’”

Collins made his debut in 1992 when, in an unusual move, the freshman running back was inserted into a game against Southwood High School in Shreveport.

He showed astounding talent in his debut, prompting one coach to wonder how he would do if he knew which hole to run through.

Collins stayed in the lineup for the rest of his high school career.

James Williams, who was offensive coordinator for part of Collin’s football career, said he was never the smartest coach.

“But I didn’t have to be,” said Williams, now superintendent of the Vernon Parish School District.

“We could be in any formation we wanted to be in but just get the ball to 32,” he said, a reference to Collins’ jersey number.

“I don’t care if you toss it to him, throw it to him, hand it to him just get it in his hands and the get the hell out of the way.”

“You can’t teach some of the cuts, some of the moves this guy would make,” Williams said.

“It was just instinct.”

Sedric Clemons, a teammate of Collins who was a standout linebacker himself, remembers the electric atmosphere in Leesville in 1995 when Collins was breaking tackle after tackle.

“You know there is some technique involved but the other is sheer will,” said Clemons, who later played on Tulane’s undefeated 1998 team and is assistant principal at Leesville High School.

Collins rushed for a staggering 3,045 yards during his senior year – 7.7 yards per carry — and scored 40 touchdowns.

He finished his four-year career with 7,834 rushing yards, another unheard of total.

Despite the gaudy offensive numbers Smith recalls a play late in the 1995 season against DeRidder.

A DeRidder player intercepted a Leesville pass, only to be tackled from behind by Collins on the five-yard-line.

Leesville put up a goal line stand and kept DeRidder from scoring.

“That is just Mr. Football,” Smith said. “That is the type of player he was.”

Collins was a 5’ 10’’ and 205-pound mix of speed and power, and he made such an impression on opponents that some sought his autograph after games.

“He ran the same 100-meter time with his pads on that he did on the track,” said Tom Neubert, who was assistant principal and principal at Leesville High School during Collins’ tenure.

“You couldn’t stop him,” Neubert said. “And if he didn’t run over you he just ran away from you.”

The town had never seen anything like Collins’ senior year.

The football program, which began in 1910, had never had much success in post-season play.

It was 1983 – nearly three quarters of a century after the school started football – before a Leesville team won a playoff game.

The 13-win total in 1995 is the first and only time that happened

The program is 489-456 with 21 ties, according to Owen’s Wampus Cat Football History.

Some seasons boiled down to whether they won over archrival DeRidder for the coveted Hooper Trophy.

But in 1995 they had to bring in bleachers to handle the crowds at Wampus Cat Stadium, which holds about 2,000 fans.

“That stadium was not only full, but people were also standing,” Williams said. “There were rows of people standing.”

“The whole parish and maybe the whole central Louisiana,” he said of fans who flocked to the games.

“People were coming from different places because they wanted to see Cecil Collins run the ball,” Williams added. “This was something that had not been done before.”

Storefronts were decorated with football signs.

Three women rushed out of a beauty salon to serenade the head coach when he was standing in line at a Church’s Chicken a few days before the state championship game.

“The buzz, it was real and it was a heck of an experience,” said Smith, who is now head football coach and athletic director of Parkview High School in Baton Rouge.

After 28 years Smith still recalls taking it all in from the end zone after Leesville earned a trip to the state championship.

“I had been there 16 years and we just never could get past the quarterfinals,” he said.

“We had just won the semifinal game at home and we knew were going to the Dome.”

Leesville lost to Salmen 39-7, finishing 4A state runner-up with a 13-2 record.

“We were outmanned,” Neubert said.

“They were much better defensively than any team we played that year.”

Collins is remembered as a happy-go-lucky, well-liked student.

“He was just a normal kid,” Williams recalled.

“Always had a smile on his face. You could tell he really wanted to be a football player.”

His mom was the night manager at a Burger King near the former Fort Polk, now Fort Johnston.

His dad was a retired military officer who took a job in Huntsville, Texas while Collins was in high school, sparking concern from school officials, later put to rest, that they were going to lose their star player to some lucky high school in Texas.

His brother James was also on the football team, serving as a blocking back for his brother at times.

Johnny Cryer, who was defensive coordinator for Collins’ senior year, used to give the star running back a ride to school from time to time.

“Cecil had his ups and downs but as far as high school he was hardworking, never missed a practice; just a pleasant kid,” he said.

The football talent was never in doubt.

“He is the best running back I have ever laid eyes on,” Cryer said.

Cryer said it is a travesty that Collins jersey number has not been retired by the school.

“But I think people are still kind of on the fence,” he said.

Collins is also notably absent from the names of star players and their jersey numbers on the front of the stadium press box, including former LSU star Kevin Mawae.

Other notable athletes who emerged from the school were LSU running backs Eddie Fuller and Michael Ford; tight end Keith Zinger and basketball star Nikita Wilson.

Cryer said when most people hear Leesville mentioned Collins is the first thing that comes to mind.

“And we can’t retire his jersey,” he said.

Collins has told friends that the days of “Cecil the Diesel” are gone, that he was headed down the wrong path during that time and might have wound up dead if he had not ended up in prison.

Smith said he understands the sentiment behind moving past “Cecil the Diesel” but still had to chuckle.

“You can’t erase what he did on the field,” he said.

Smith recalls being in Fort Lauderdale, Fla, in 2015 to celebrate his 25th wedding anniversary when Collins insisted on taking the couple to dinner.

“He owns up to his mistakes,” the coach said.

He said his two daughters regard Collins as the brother they never had.

“I would let him stay with my daughters if it came to that,” he said.

“That just tells you the trust that my wife and I had.”

Collins said he considers Smith like a second father.

“He was knocked down to the lowest from where he was,” Smith said.

“To see where he is today . . . If God can forgive me for what I have done, then I believe he can forgive Cecil.”

Neubert said Collins inability to win admission to the sports hall of fame points up the community divide nearly three decades after he left.

“I think he deserves to be in the hall of fame,” he said.

“He made a mistake, but he made it out and then he reclaimed his life.”

Clemons also said Collins belongs in the hall of fame.

“My gosh, it is time,” he said.

“It is time because of what he has done for Leesville High School as an athlete.”

“He served his time. It is time for forgiveness, and it is time to honor this man for what he did athletically.”

“He is the standard,” Clemons added. “I don’t care who comes after him.”

Insiders say there is more to the story of Collins’ conviction than most people know.

Others question if 13 plus years fit the crime, and whether Collins was the victim of some bad luck on top of some bad judgment.

Richardson said Collins’ life includes lots of what-ifs.

He and others are often reminded of Collins short, spectacular career at LSU, including a 232-yard game in 1997 against Auburn on national TV in one of his first times on the field.

In just four games he rushed for 596 yards, averaging 8.3 yards per carry.

Announcers raved about his special talent, and how he might threaten playing time for then injured LSU All-American Kevin Faulk, a star at Carencro High School who later earned three Super Bowl rings as a key player for the New England Patriots.

“He is the best running back I have ever seen in person,” Faulk said.

He said that, during Collins’ freshman year when he could not play with the varsity, he was running plays for the scout team and causing problems for LSU’s first team defense.

“That was probably the best back they saw all year long,’’ Faulk said with a laugh.

“He was just gifted. His talent was just unmatched. Gifted and strong. Had great balance.”

“He wasn’t the fastest, but he could run away from people,” Faulk said.

Even today LSU fans wonder how things might have turned out if Collins had not suffered a broken leg against Vanderbilt, never suiting up again for the Tigers.

“It is a tragic story,” Richardson said.

“It would be a tragedy if he was just a regular person. He had a special talent and a bright future and that made it even worse.”

Collins has returned to Leesville a few times since he got out of prison.

His picture made the rounds on social media last year when he was sitting in the stands for a game.

“I think the town misses him,” said Owen, who is also a state representative.

“This is a church community and there is a permeating belief in redemption.”

Collins has told people he wants to be judged for the man he is today, not 10 or 15 years ago.

“He just wants to move forward,” Faulk said of his former teammate, and the two former running backs stay in touch.

Collins said he has fond memories of his heyday in high school.

“My teammates, I made some good bonds man.”

“It was really good. Everybody I played with, we played from junior high on up.”

“That was really cool,” he said. “That is what made the time so great.”

“You don’t realize how special until later in life,” Collins said.

Be the first to comment