Once upon a time in the mid-1960s through the late 1970s in the Airline Park subdivision in Metairie, Mike Miley was a touchdown throwin’, home run hittin’, jump shot swishin’, track jumpin’ phenom.

Word of his athletic prowess spread.

You gotta see this kid play quarterback! You gotta see this kid play shortstop! You gotta see this kid play guard! You gotta see this kid high jump!

When Miley’s sports seasons overlapped, he instantly transitioned. Hit a home run, take off baseball cleats, slip on track spikes, run over to the track and win the high jump.

“Mike was the best athlete that I ever coached,” said Joe Brockhoff, who was Miley’s East Jefferson High baseball coach when the Warriors won the 1971 state Class 4A baseball championship. “And he was always just a good person to be around. Always easy to deal with, never too full of himself.”

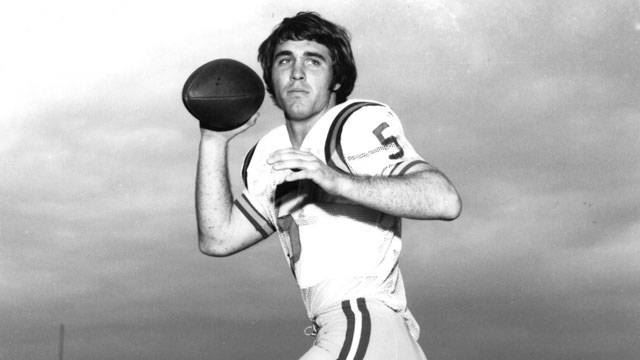

Miley, twice a Major League Baseball first-round draft choice, a starting quarterback at LSU and an All-American shortstop, played with quiet passion. His “it’s not over until I say it’s over” approach earned him the nickname “Miracle Mike.”

“Mike never thought he was going to lose,” said Barry Wilson, who coached Miley on LSU’s 1971 freshman football team. “He always thought, `Hey, in the last-minute I’ll win it.’”

And because Miley stood 6-1 and was a rather thin 185 pounds, he looked like the kid next door because he WAS the kid next door.

Except as Miley’s LSU baseball teammate Dennis Lorio so accurately described him, “He was better than everybody else.”

Coaches loved him because he was a star who was coachable. Teammates respected him because they knew they always had a chance to win with him in the lineup. Fans showed up to watch him play because he would provide special moments.

And they all were shocked that fateful January 1977 night when Miley was tragically killed in a one-car accident in Baton Rouge. He was 23 years old, one month from likely becoming the starting shortstop of the California Angels.

His loss was greatly mourned and still is by those who he touched directly or indirectly by simply being a great athlete and an even better person.

More than 43 years later after his death, 70-year old plus men who coached or played with and against Miley still hold him in reverence. Mention his name and they are young again, enthusiastically recalling his athletic feats and admiring his humble persona.

Miley Memories from Danny Emmons, a teammate of Miley at T.H. Harris Jr. High and East Jeff:

“Our ninth-grade year (at T.H. Harris), we won every title – football, baseball, basketball and track. Our letter jackets had a lot of championship patches.

“Mike always came up with the big play. We played baseball against Marrero on a Westbank field. They had a guy pitching who looked like a grown man, but Mike hit a game-winning home run off him. They were so upset about losing I thought they’d have to call the cops to get us out there.

“During Mike’s senior year at East Jeff, me, Mike, John Burks who was Mike’s best friend and his favorite receiver and a guy named Mike Miller drove from New Orleans to Miami to watch LSU play in the Orange Bowl. LSU was recruiting Mike and John, so we all had free tickets.

“It was shocking that our parents let us go on the trip. We went in my new Roadrunner my Dad bought me. It took us forever to get there and back. After the Orange Bowl game, we all got caught up in a mini-riot on the Miami Beach strip and we were running for our lives.

“I was living in Slidell when Mike died. I went to the funeral. I think everybody in Jefferson Parish did, too. Incredibly sad.”

Phenom in the making

The legend of Mike Miley started when he attended T.H. Harris Jr. High, not far from his Airline Park home. He quickly became the idol of the neighborhood kids.

One summer in an American Legion All-Star game at Airline Park – which was re-named Mike Miley Playground and Park just days after his death – 12-year-old Scott Smuck and other Airline Park kids were in awe watching a 14-year Miley launch home run after home run.

“We stood behind that Airline Park backstop on the corner of Sadie Avenue and West Metairie Avenue, directly behind the catcher,” Smuck recalled. “Mike’s just smacking homer after homer, bouncing them off the roofs of houses and garages on Phillip Street.”

Brockhoff first coached Harris Jr. High in Metairie and got a glimpse of his future East Jeff High star when his teams faced Miley’s T.H. Harris squads.

“Natural is a popular word in athletics, but Mike truly was a natural,” said Brockhoff, who also was Tulane’s head coach for 19 years through 1993.

Elton Lagasse, who was an East Jeff football assistant as a line coach, doubled as the school’s head track coach. Looking at his lineup one day, he needed a high jumper who could get him points in a meet.

Why not use Miley, the best athlete in the school? Lagasse had seen Miley play basketball, so he knew he had hops.

“I asked Joe if I could borrow Mike from baseball for track and he said it was OK,” Lagasse said. “I gave Mike a uniform, he goes out in his first meet, clears 6-2 and wins.

“I said, `Man, I got me a winner here.’ I go back to Joe and ask, `Can I have him a couple of days a week so I can work with him in practice?’ Joe agreed. Within two weeks, I had coached Mike down from jumping 6-2 to 5-8. From then on, I told Mike, `The uniform is in the locker, just go put it on for the track meets.’

“I learned when you get a good athlete, you leave him alone.”

Miley was a star in every sport he tried, evolving into a two-time all-state selection in football and baseball for East Jeff where he was the starting quarterback and starting shortstop for three years. A rollout passer and an elusive running threat – Miley always did his best work on the move – he had 2,123 yards total offense (1,452 passing, 671 yards) as a senior and accounted for 28 TDs.

Ole Miss wanted him to sign him as a two-sport star, slotting him in the starting quarterback/shortstop mold of Rebels’ legend Archie Manning who finished his college career at the same time Miley concluded at East Jeff. Legendary Alabama coach Bear Bryant also chased Miley.

Miley signed with LSU, but the Tigers’ football coaching staff thought there was little or no chance he would enroll because he was a projected first round MLB draft choice.

“I was in shock when Mike decided to come to LSU, we were lucky to get him,” said Wilson, a former star New Orleans Holy Cross High and LSU center who became the LSU assistant coach responsible for recruiting Miley. “I really believe he wanted to play baseball, but his family wanted him to go to LSU to play football. Baseball was his love.”

Miley truly loved baseball and baseball loved him back.

There were always several major league scouts and college recruiters in the stands at almost every East Jeff baseball game and most of the practices.

“What Mike went through was enormous, none of us had ever experienced it,” Brockhoff said. “He was constantly bombarded by scouts and recruiters. It was something special watching him handle all that and keep playing well. His maturity was through the roof.”

Once, Miley was putting on a private hitting session for scouts with Brockhoff throwing the pitches. He kept ripping pitch after pitch into left field until one scout muttered “Can he hit to right (field)?” loud enough for Brockhoff to hear.

Brockhoff put the next pitch on outside of the plate and Miley cracked a laser beam that hit the right field foul pole on one hop.

The scout immediately and dutifully scribbled in his notebook – “CAN HIT TO RIGHT.”

Miley concluded his high school career by leading East Jefferson to the state baseball championship, fulfilling a commitment he and the rest of the team made the previous year when East Jeff was knocked out of the 1970 state tournament.

Miley, then a junior, felt responsible for the elimination game loss. He committed a throwing error allowing the go-ahead run. Then, with the bases loaded and two outs in East Jeff’s last at-bat, he scorched a line drive off the pitcher that caromed to the second baseman who threw Miley out.

Miley, not used to failing in the clutch, cried as his teammates consoled him. They let him know the team wouldn’t have made it that far without him.

Those who knew Miley said his throwing error haunted him all the following summer.

The next year as a senior, Miley was hitless in East Jeff’s state tourney opener. In the second game, he worked the opposing pitcher into a 3-0 count in his first at-bat.

“Mike looked at me coaching third base and I gave him the hit sign,” Brockhoff said. “He hit a bomb out of the park. When he trotted around the bases and came around third, he said, `Thanks, Coach,’ I needed that.’ I said, `You’re welcome.’ After that, nobody really got him out and we won that state tournament.”

All that was left for Miley, who hit .413 as a senior, was the MLB Draft. Would a team pick him high enough and offer enough money to have him renege on his LSU football scholarship?

“Mike was projected after his junior year going into his senior year as the No. 1 overall pick in the draft,” Brockhoff recalled. “Because he had signed with LSU, major league teams couldn’t get a commitment from him that he’d give up his football scholarship to play pro baseball.”

It scared away every team in the first round except one. The Cincinnati Reds took Miley with the last pick of the first round. He was drafted five and six spots ahead respectively of future Hall of Famers George Brett and Mike Schmidt.

“I came very close to signing,” Miley later told New Orleans States Item sports editor Pete Finney. “Their (the Reds) last offer (with a $65,000 bonus) was very attractive.

“Why didn’t I sign? Well, I felt I’d always regret it if I didn’t give football a whirl. I’ve been second-guessed as a quarterback and I didn’t want to be second-guessed at this. So, I made the decision, the biggest of my life.”

Miley Memories from Woody Wells, one of Miley’s East Jefferson High assistant basketball coaches:

“When I got to East Jeff as a coach, Bobby Bowden, who played basketball for East Jeff and later played at Southern Miss, told me about Mike. He said, `He’s the hardest working athlete you’re ever going to see here at East Jefferson. He’s such a natural athlete and such a good guy that everyone wants to see him succeed.’

“I played some pickup games with Mike. I was amazed how fluid he was. There’s not a doubt in my mind he could have also played basketball at LSU, but he was already being pulled in different directions.

“He was such a genuine person. He said hello to everybody. He didn’t care if you played ball or not. He wanted to talk to people and learn about them. He never forgot anyone’s name. He was a good teammate, a good guy and a good student. I don’t think enough has been done at East Jefferson to honor him.

“I was living in Houston when I learned Mike passed. I read it on a sports ticker he was killed in a one-car accident in Baton Rouge. I had no idea where it happened, but I immediately wondered if he had run off Highland Road.”

A Baby Bengal and a Tiger

As expected, Miley had an immediate impact as a freshman on LSU’s baseball team.

“Mike’s first time around the SEC, there wasn’t much scouting done by opponents,” recalled Lorio, who was a multi-positional outfielder for the Tigers. “Everybody tried throwing fastballs past the freshman. Back then in a season with fewer games than LSU plays now and using a wood bat, he hit eight home runs (also for a .333 average). He just whipped that bat around.”

At that time in college football, the NCAA ruled freshmen weren’t eligible to play for the varsity. Schools had freshman teams and LSU’s was nicknamed the Baby Bengals.

Former LSU running back Brad Davis was in the 1971 recruiting class with Miley. In the Baby Bengals season opener in Oxford against the Ole Miss freshmen, Davis quickly learned why Miley was so heavily recruited.

“We led by two or three touchdowns, but Ole Miss came back on us and took the lead,” Davis said. “Then, we got the ball back one more time and that’s when Mike got his nickname `Miracle Mike.’”

Despite being sacked for a 13-yard loss, an unruffled Miley completed passes of 22, 38 and 12 yards on the final drive, the last completion the game-winning TD in a 33-28 victory to begin what transpired as a 4-1 season.

“We called the (last) play and Mike actually changed the play offering a suggestion,” said Wilson, who along with ex-LSU quarterback Nelson Stokley, served as co-head coaches of the freshman team. “Nelson and I both told him, `Go with it.’

“Mike just made things happen. You rarely thought he was ever going to lose and that’s the way he approached it.”

On the freshman team, Miley had 870 yards total offense in the five-game season, passing for 744 yards and six TDs.

“I always thought Mike was a little ahead of his time,” Wilson said. “He was better on the move. He threw the ball well and he was extremely accurate. He would have fit today’s style of run-pass option offenses perfectly.

“But back then, we were only throwing about 15 times a game. He really wanted to be a passing quarterback, but it just wasn’t happening in that era.”

When Miley joined the LSU varsity as a sophomore in 1972, he was third on the depth chart behind seniors Bert Jones (a first-round NFL Draft choice in 1973) and Paul Lyons. LSU coaches wanted Miley to redshirt. When he balked, the coaches tried other ways to utilize his skills.

He returned punts and kickoffs, and even had three rushing attempts. The coaches wanted Miley to play defense, but he didn’t want any part of that temporary position switch.

In the spring practice of 1973 when Miley was elevated to starting quarterback for his upcoming junior season, balancing football and baseball responsibilities required his ultimate time management.

“Mike would take batting practice in football pants and cleats,” former LSU first baseman Wally McMakin recalled. “He’d dress in the Tiger Stadium dressing room and walk across the street to baseball practice carrying his jersey and his football helmet stuck through the middle of his shoulder pads.

“He set them next to the batting cage. After he got his swings, he’d grab his stuff and walk across the street to the Ponderosa for football practice.”

Miley never missed a baseball game because of football practice. But in April 1974, LSU’s spring football game was scheduled on the same day as a Tigers’ baseball doubleheader at Ole Miss.

“Mike finished the doubleheader and ran to a car waiting for him that took him to the (Oxford) airport,” Lorio recalled, “to fly him back to Baton Rouge for the spring football game.”

It had to be exhausting. But by that time, Miley already knew his next career move.

Miley Memories from Don Griffin, Miley’s backup quarterback at LSU in 1973:

“We were very close. We hung out a lot together. He was the coolest cat on the field and off the field, but also the kindest, nicest guy.

“I played behind him and I wanted to play, but as long as Mike was in there, I was like `I think we’re doing good.’ He was so smooth. You didn’t realize how fast Mike was until you tried to run with him. He was at least 6 feet, a little more. Just as beautiful to watch on the baseball field as he was in football. No useless effort. Just everything designed to get it done.

“I compared Mike’s play to the way Archie Manning was at Ole Miss. You better keep your eye on him on the field because Mike’s about to do something and you’re going to miss it.

“He was just a prince of a guy. When I transferred to Southeastern, he came over to watch me play during his pro baseball off-season and did stuff after the game with me. He was just so thoughtful.

“When Mike died, part of why he was in town was he was going to come that week to my wedding. His loss still hurts.”

Nine consecutive wins, three straight losses

Miley, like many quarterbacks who played for LSU head coach Charles McClendon, tried to mesh with McClendon’s two-QB system.

McClendon substituted his QBs on a pre-determined series instead substituting on a need-basis. Being pulled in and out of games, especially when he and the offense were in rhythm, was maddening for Miley, who was the starting QB in all of LSU’s 12 games in ’73.

“Mike’s the kind of quarterback you have to get used to,” McClendon said after the first four games. “He’s a scrambler, but we haven’t really been equipped to play with him yet.”

At season’s end, Miley’s stats on paper were not overwhelming – 978 yards passing with a 7-to-10 touchdowns-to-interceptions ratio, 216 yards rushing and four TDs.

Yet almost every Saturday, he’d make a play that would change game momentum.

“Mike was good in practice,” Griffin said. “But turn the lights on Saturday night, look out. Brother, he could go. Put him in a situation and he would beat you. When nobody else could make something happen, Mike could make it happen.”

Like his 30-yard third-quarter TD pass to Ben Jones to break a scoreless halftime tie in the ‘73 season opener vs. Colorado. Or his 45-yard run to set up a Davis TD on the opening second half drive against Texas A&M. Or his scrambling 51-yard pass to Al Coffee to set the table for a lead-taking TD run by Davis vs. Auburn. Or scoring the game-winning TD with a minute left as he took the Tigers the length of the field for a victory at South Carolina.

“When Mike walked into the huddle, there was a sense of anticipation,” Jones said. “He had the `it’ factor, whatever `it’ is.”

With Miley engineering the offense, LSU was 9-0 and ranked No. 7 in the nation. But the Tigers lost their last three games by a combined score of 51-16, closing the regular season with losses to No. 2 Alabama and Tulane and then to No. 6 Penn State in the Orange Bowl.

By the time spring practice rolled around a few months later, LSU had changed its offense from McClendon’s traditional I-formation to the option-run oriented Veer. The reasons were to take advantage of Miley’s running skills and hopefully sway him from leaving school if he was again a first-round MLB pick in the June 1974 draft.

“The coaching staff convinced Coach McClendon for us to keep Mike from leaving to play major league baseball, we needed to run a split-back Veer,” Wilson said. “Coach Mac knew the kind of player Mike was and was willing to make that change.”

Davis said Miley and the Veer, which was the offense employed on the Tigers’ 1971 freshman team when Miley was QB, were a match.

“We went through spring practice in ’74 and Mike was terrific in the Veer,” Davis said.

Miley never tipped his hand to his football teammates about future career plans. But his baseball compadres knew what was coming.

“Mike never really got along with (offensive coordinator Charlie) Pevey,” McMakin said. “He was miserable with football and how they were treating him. They treated him like a dog. Mike told us, `If I get drafted high enough, I’ll probably sign and leave.’ He had an option to haul ass and he did.”

The Angels drafted Miley, who had an LSU career .280 batting average, as the No. 10 overall pick. He signed and collected a reported $90,000 bonus.

“I begged him to come back, but I didn’t blame him,” Davis said. “That was a lot of money back then.”

About 1½ months after the draft in late July, Miley was already playing for Class AA El Paso in the Texas League when he expressed some of his LSU football career frustration in a column written by Alexandria Town Talk sports editor Bill Carter.

“I felt that we lost to Penn State because Coach McClendon had lost confidence in me,” Miley told Carter. “We should have beaten Penn State. But we didn’t play the kind of game that was necessary to come from behind when they got ahead. I had been throwing some interceptions and he (McClendon) wouldn’t let me use the passing game that we needed.”

Without Miley at QB in 1974, the football Tigers stumbled to a 5-5-1 record, something Davis still believes could have been avoided.

“It’s always bothered me that we could have gone back and run the I-formation without any trouble,” Davis said. “But the coaches just wouldn’t switch back. We didn’t complete a pass until the fourth game of the season. Without Mike, you could see what was coming.”

That season was the beginning of the end for McClendon. He never again had a 9-win season after Miley’s only year as a starter and was forced to quit at the end of the 1979 season after 18 years as head coach.

Baseball, however, shockingly won the 1975 SEC championship the season following Miley’s departure. It was the school’s first league title in the sport since 1961.

Miley quickly advanced to the majors, playing 84 games for El Paso in ’74, followed by 81 games in 1975 for the Class AAA Salt Lake City Gulls before being called up to the Angels for 70 games. He opened the 1976 season back at Salt Lake but earned a September call-up to the Angels for 14 games.

Though Miley had just a .176. batting average in his 84 games with the Angels, his flawless fielding and his speed on the base paths made him the favorite to become the Angels’ starting shortstop once spring training opened the following February.

“He has everything it takes, he’s big league material,” said Dave Garcia, Miley’s El Paso manager.

Miley Memories from Dennis Lorio, one of Miley’s LSU baseball teammates

“Mike was a phenomenal fielder. One time, we were leading Mississippi State. They had the bases loaded and they hit one up the middle. Mike made a play (former LSU starter and current Houston Astros infielder Alex) Bregman makes now. He catches it going his left, then spins all the way around and throws out the runner at first.

“He could run, hit, throw, he had some power. Everybody knew that’s what a major league guy looked like. He had all the skills and the temperament and was just a great guy.

“He knew he was going to be a future major leaguer, but the beauty of Mike was he was as down to earth as could be. He’d make a great play and I’d say `Damn Mike, that was unbelievable.’ He’d just smile at you. He was so gifted, so humble and not cocky.

“It was an honor playing with him. All of us anticipated him playing in the major leagues about 15 years and I could say, `Hey, I played with Mike Miley, that’s our guy out there’ just like we do right now with Bregman.

“It was a real tragedy when we lost Mike.”

Unspeakable heartache

Highland Road stretches 14½ miles in Baton Rouge from Government Street on the edge of downtown to Airline Highway. As the years pass and the city expands, Highland covers a varied demographic slice.

It runs through the middle of the LSU campus sandwiched between such neighborhoods as the multi-million opulence of the Country Club of Louisiana near Interstate 10 and the shotgun houses, run-down convenience stores and empty lots in the low-income area known as The Bottom not far from the north gate of LSU.

Even now with more developments and businesses between Lee Drive and I-10, driving that stretch of Highland Road with its moss-covered trees and its curvy winding two lanes requires total concentration, especially at night.

Imagine the same section of Highland four decades ago with much less development and fewer streetlights.

“I can’t tell you how many times I went down Highland Road to the bars, then tried to make it back home,” Davis said. “I’m lucky to be here.”

In the first week of 1977 a month or so before spring training when Miley was set to make a push to become the Angels’ starting shortstop, he was back in Louisiana.

On the night of Jan. 5, 1977, Miley partied in Baton Rouge with some of his former LSU baseball teammates. They drank past midnight until around 1:45 a.m. when the gathering broke up.

Miley was legally drunk, according to a Louisiana State Police crime lab test released a week after what happened when he got in his new sports car – a Datsun 240Z – with his driver’s side window down and wearing no seat belt. He sped off on Highland headed home to Metairie.

Baton Rouge police said about 1:50 a.m. Miley’s car ran off the right shoulder in the 7800 block of Highland 140 feet west of Rodney Drive, which is between Kenilworth Parkway and Staring Lane. His vehicle crossed the centerline, ran into a ditch on the left side of the road and skidded sideways on the shoulder striking eight posts before flipping over.

Miley was thrown through the open driver’s side window and the car rolled over him.

“We think he lost control and failed to make a curve,” then-Baton Rouge police chief Howard Kidder said. “There were no witnesses, but a resident of the area heard the car hit, ran outside and then called police. The police arrived and Miley was dead at the scene.”

Word spread before sunrise.

“It’s terrible, just terrible,” McClendon told the Baton Rouge State-Times newspaper. “It’s regretful anything like this could happen to a young man like Mike Miley with such a bright future ahead of him.”

Then-LSU baseball coach Jim Smith said in a newspaper report that Miley visited him on the day of the accident.

“I spent an hour with him, and he was in good spirits,” Smith said. “He said the Angels had treated him well with his contract and he was really looking forward to spring training.”

Brockhoff, about to start his third year as Tulane’s head coach, was driving home after a recruiting trip in Florida. He learned of Miley’s death as WWL-AM in New Orleans delivered the awful news over his car radio.

He had to pull off the road.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Brockhoff said. “It’s not something in any way you can believe would happen. I was just devastated. The first thing I thought about was his Mom and Dad (Wilfred and Ruth Miley). They were absolutely fantastic people. They were the reason the way Mike was, because he came from a great family.”

Miley Memories from Pat Artieta, Miley’s older sister who’s had a career as high school teacher in Baton Rouge and along with her husband Butch raised two baseball-playing boys Corey and Clint who now have their own families

“When we grew up in Metairie in Airline Park, we had a precious little family. I was four years older than Mike and my sister Jan and I are 10 years apart. My Mom and Dad (Ruth and Wilfred Miley) were wonderful parents, they did everything they could for all of us.

“My Dad was from Newton, Miss. near Meridian, my mom was from the Delta. My Dad played football for Memphis State, so I was born in Memphis when he was graduating. Mike was born in Yazoo City, Miss. where my Dad’s first job out of college was located. He started working for B.F. Goodrich and was with them for about 50 years. His job brought us to Metairie.

“Everybody felt like Mike was their good friend. He was the kind of person who put you at ease and made you feel like you were the most important person he was talking to.

“When the coaches said something to spotlight him, Mike didn’t want it to be about him. He never did. He just wanted to win and be part of the team.

“Any sport he played, it came effortlessly. He was Mr. Biddy Basketball in New Orleans when he was about 10 years old. My Dad used to think Mike’s best sport was basketball.

“Mike was a really precious human being. The way Mike treated everyone is a lesson for people to understand that you can be successful and talented, but you can also be a good human being. It’s a tribute to my Mom and Dad. They raised us in a way I wanted to raise my kids.

“When Mike died, it was a shock for all of us. But for my parents, it just broke their hearts forever.”

The best brother ever

Just days after the accident, Pat Artieta wanted to visit the crash site where Mike died.

“I was determined to go to the place where it happened, where Mike was last alive,” she said. “My husband told me it wasn’t a good idea and I clearly wasn’t thinking straight. I thought, `Maybe if I go there, I’ll find out it was a horrible mistake.’”

But it wasn’t. Pat saw concrete poles that had been knocked over by the impact of Mike’s car. Until this day, she tries to avoid driving that route.

When Mike died, Pat had almost a four-month old baby, Corey, her first son, who eventually played college baseball for Louisiana-Monroe and spent three years in the Milwaukee Brewers organization as a lanky 6-6 lefty pitcher.

“After Mike found out I was having a boy, he was just thrilled,” Pat said. “He decided he was going to learn how to cross-stitch because he wanted to give his first nephew something special. He said, `I heard cross-stitching is great for your dexterity.’

“He cross-stitched this birth announcement thing for Corey. He had Corey’s name, his date of birth, his weight, but Mike didn’t get to finish it. Years later, I had one of my students who could cross-stitch finish it and I gave it to Corey.”

A month after Corey was born, Pat said her brother stayed a week with her and husband in October 1976.

“Mike wanted to hang out with Corey,” Pat said. “I was so glad I got to spend time with him because he was gone a lot.

“He was just that thoughtful, he really was. He always kept in touch. He was a good letter writer.”

The day Mike died, he had driven from Metairie to Baton Rouge for a full day of visiting friends. His first stop was Pat’s house to deliver something from their mother.

“I was usually at home, but I wasn’t home when Mike came by,” Pat said. “I’d probably gone to the grocery store. I always regret that I wasn’t home. But, who in the world would ever dream that would have been the last time that I could have seen him?

“Mike wasn’t a wild and crazy guy, he wasn’t a partier. That night, after running into all his friends and going out to dinner, he was drinking. having fun with his college baseball buddies and one thing led to another.

“He probably should have stayed in Baton Rouge, but Mike told my mother earlier he was going to come home. He was that kind of guy. If he told my Mom he was going to come home, he was going to honor it, even if he was a 23-year-old grown man.

“My Dad was out of town in Kansas, so my Mom and young sister were home alone when somebody came to the house and told them about the crash.”

When Pat thinks about her brother, she mostly remembers the joy he brought to his family.

She recalls the time Charlie McClendon and his wife Dorothy Faye paid the Mileys an in-home recruiting visit.

“Mom and I were running around with chickens with our heads cut off making sure everything was ready,” she said. “We all had a little something to eat and then we went to East Jefferson Stadium to watch Mike play. Everybody in the stands was like, `Charlie McClendon is here!’

Or watching Mike play football in Tiger Stadium.

“I used to get so sick to my stomach I could barely sit in my seat, so I would walk around and around,” she said. “You could hear some terrible things being said in that stadium regarding your family member when you were trying to cheer for him.”

Or when the entire family was on hand to watch Mike hit his first major league home run.

“Mike hadn’t hit well to that point,” she said. “I can still see Dad pacing, pacing, pacing and then in one of Mike’s last at-bats he hit a home run. It sure helped our trip home. Dad was really happy about that.”

It’s natural there’s still lingering pain for Pat, particularly when she recalled just before Mike’s death he had just signed a contract guaranteeing he’d play at least 100 games with the Angels in the ’77 season.

“Mike worked hard all his life, he was right on the doorstep,” Pat said. “We were all so happy for him. It was just getting ready to happen in that next moment, and it just didn’t. When you’re getting ready to live your whole dream, it’s just unthinkable that (the wreck) could happen.

“I’m a Christian and I know the Lord has a plan for all of us, but I really feel Mike wouldn’t have gone home that night had my Dad not been out of town. I believe he didn’t want my mother and sister to be alone.

“When I get to Heaven, I want to ask Mike about that one.”

Miley Memories from Lee Rhodes, who coached Miley in football, basketball and baseball at T.H. Harris Jr. High

“Mike is the best athlete still to come out of Jefferson Parish.

“One time, he walked in my office and he was concerned about how his getting too much attention affected his teammates. He said, `Coach, you’re using me a lot to demonstrate your points to the players. Please, do me a favor and spread it around.’ I heeded his advice and it stuck with me the rest of my coaching days. Mike made me a better coach.

“I still get emotional when I talk about Mike. His funeral at Egan Funeral Home on Veterans Highway is the largest I’ve ever attended. It’s unbelievable the following Mike had. Dick Williams and other coaches from the California Angels were there. All his LSU, high school and junior high coaches were there.”

Time passes, but the hurt never fades

Twenty-five years after Miley’s death, New Orleans Times-Picayune sportswriter Bill Bumgarner contacted the Miley family because he was doing a story on various venues in the area named for athletes, such as Mike Miley Park.

“I called his mother, she answered the phone and she was very nice,” Bumgarner said. “When I finished the interview, I said, `Mrs. Miley, I really appreciate the time. Can you tell me one last thing about Mike?’”

“She said, `He was a very, very nice boy’.”

Ruth Miley died in November 2016 at age 85, almost 14 years after Wilfred Miley passed away in January 2003 at the age of 75. He was laid to rest next to his only son exactly 26 years to the day of Mike’s death.

Long after their son passed, the den in the Mileys home remained the same as the day he died, still filled with his trophies and awards on display. His parents hung on to his memories like many of his former coaches and teammates continue to do.

Just a couple of days before his death, Miley went to Clearview Mall. He walked into Schumacher’s, which at one time was New Orleans’ oldest continually operating shoe store. He had a pair of boots that needed repairing.

Behind the counter was Scott Smuck.

Remember him? The neighborhood kid who marveled watching Miley unleash a barrage of home runs in an American Legion all-star game?

Miley handed Smuck the boots and suddenly Smuck felt like he was 12 years old again.

“I’m not one to get star struck, but Mike had that effect,” Smuck said. “I was like `I can’t believe Mike Miley is standing in front of me.’”

Smuck was also just as stunned less than 48 hours later when he learned Miley’s boots would never be retrieved by his owner. He could have kept them as a collector’s item, but he knew he had just one course of action.

“I donated them to Goodwill,” Smuck said. “Who was going to fill that guy’s shoes?”

Ron, Your article was fine until you insulted my parents’ and their life after Mike’s death. Whoever you talked to about them is no friend of Mike or my parents. You know NOTHING about their life! Gossiping is not journalism.

I guess talking to your sister is gossiping, Jan.

I knew Mike from playing ball with him at Airline Park playground to T.H. Harris and later on at E.J.

Everything said about him in this article is absolutely true. He was the best pure athlete ever to come out of Jefferson parish even to this day.

Athletics aside probably the best thing about him was the kind of person he was. He was always a very genuine and really nice person. He always had time for anyone who approached him and he was very approachable. You didn’t have to be a jock.

He was the real deal.

I’ve read this story a dozen times, and I’m not sure why his sister objected to part of it. Unless she was upset by the fact they kept his memories out and on display. In any case she was there, so I believe her. But I thought it was one of the best compilation of memories by his friends, coaches and team mates I ever saw. I was in schools with Mike and we are the same age, so he was in some of my classes. (Airline Park, TH Harris, and East Jefferson HS) I played little league baseball briefly with him at Airline Park Playground, (Now Mike Miley Field). We rode bikes down the same street to go to school, as we both lived in Airline Park. I broke my back as a child and so I live vicariously through Mike’s deeds I wished I was him. I physically can not run (I would pass out due to pain). That is why I little league days ended when I tried to run for a pop up fly, and fainted and fell. The coaches found out about my broken back and would not let me play any more. So I saw Mike as running for me. Of course he was running for himself and teammates, but I decided he was doing for me, since I couldn’t. When Mike died so did a part of me, as it did for so many people from Metairie. I still have a pile of his rookie cards. God bless Mike Miley.

The sister quoted in the story loved it. The other sister didn’t. Nevertheless, I loved writing this story. Mike was a special athlete and person.